23/01/2024

Borrowed money – borrowed time

Newsletter #66 - January 2024

A soft landing!

Former UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson is often attributed with the phrase “a week is a long time in politics”, and now it seems as if the financial markets believe that two months is a long time in economic terms.

In November and December 2023, the financial markets and most economists turned from anticipating a major recession to forecasting a soft landing – based upon an expected fall in inflation and a press conference given by Federal Reserve Chair Powell.

A year ago, most economists expected a recession in 2023, with high inflation and negative growth. Now, they expect a soft landing with low inflation and growth, on the assumption that the central banks will lower interest rates between three and eight times in 2024.

We were sceptical of the recession forecast, and now we are sceptical of the ability of the central banks to create a soft landing.

Our doubts are anchored in two particularly important economic factors that have been overlooked in the current debate:

- the unemployment rate;

- general government deficits as a percentage of GDP.

Unemployment at 40-year lows

As we have previously argued, there are only two possible ways to increase production, either by adding more hours worked or raising productivity - and productivity has been falling lately, as we have also previously mentioned.

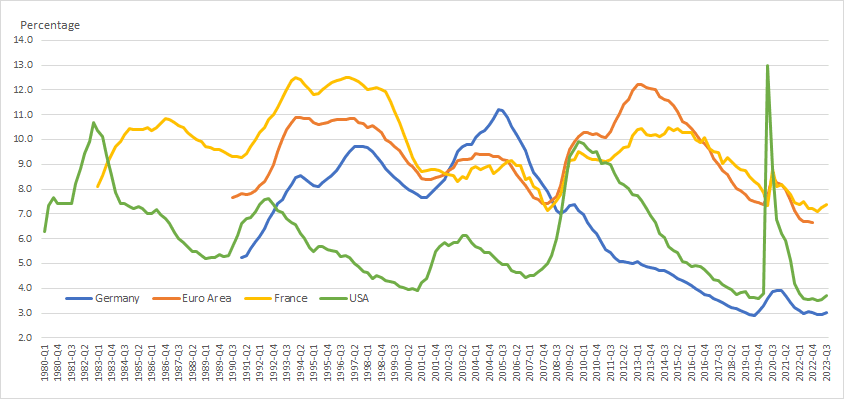

Adding more hours can be done by increasing employment, with a corresponding decrease in unemployment. Figure 1, below, clearly shows that unemployment levels in the eurozone (and in detail for Germany and France) and the US are at their lowest levels since 1980. There is simply not a lot of the unemployed around to add more hours.

Even COVID-19 caused just a blip on the radar, lasting only two quarters.

Figure 1 Unemployment rate since 1980 source OECD Data

Throughout 2023, there were no signs that unemployment was about to rise significantly. And it is difficult to have a recession if employees are not laid off.

Over the last 40 years, unemployment has been on a long-term downtrend, especially since the financial crisis of 2008. Overall, this should be good for the economy and, especially, for public finances.

When unemployment falls, the public sector benefits in two ways: firstly, the cost for unemployment benefits, which is one of the largest variable items in the budget, falls quickly; secondly, tax revenue also increases, improving the public sector balance even further.

Given the 40-year low in unemployment, public finances should be in really good shape at the moment.

Unfortunately, this is not the case.

Borrowed money

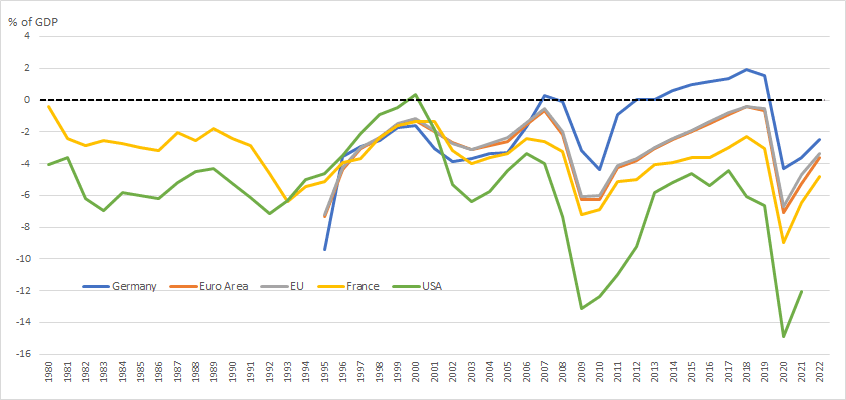

While employment has seen gains, and unemployment fallen, public finances have not progressed. Or rather they have, but governments have unfortunately decided to spend the additional revenue, with the result that public finances in general have not improved, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2 General Government Deficit as percentage of GDP source OECD Data

It is important to point out that the public sector is not, and should not, be compared with a private household, as some commentators tend to do.

Public finances can run a sustainable deficit over time as long as growth in nominal GDP outpaces the deficit as a percentage of GDP.

Since the financial crisis of 2008, many countries have been running unsustainable deficits. Germany was an exception for a few years but, during the pandemic, Germany again ran a large deficit in the general government account from which it has still not recovered.

Even more worrying is the deficit in the US. The as yet unpublished figures for 2022 and 2023 should show a deficit of approx. 4% and 8% of GDP, respectively, according to the IMF’s forecast; the IMF expects this deficit to remain at around 7% of GDP in its forecast for 2024-2026. That is a lot faster than the development in nominal GDP, which puts the US on an unsustainable path of more debt and higher interest payments.

In the EU, it is also difficult to see any significant improvement in public finances, as private consumption and investment are slowing down due to higher inflation.

As public debt continues to grow, interest payments on that debt will soon increase the deficits in the public sector.

Public deficits of this size are a major factor in maintaining GDP growth rates.

With the presidential election in the US looming in November 2024, the public spending spree will most likely continue.

Therefore, we are probably looking at three quarters of growth driven largely by public spending and accompanied by attendant volatile inflation data.

The only problem is that borrowed money, i.e. running public deficits, can only be spent once. Eventually, the borrowed money will have to be repaid sometime in the future.

In other words, governments are currently using future consumption to boost present consumption in order to please their voters today.

On borrowed time

When interest rates are close to, at or below zero, it is easy to borrow and spend on public consumption. It is also the right time to make structural reforms because they are easy to fund.

However, for the big economies in the EU and the US, structural reforms are rare indeed. In Germany, no major structural reforms have been introduced since Hartz IV in 2003. In France, any structural reform is almost impossible to implement, or even discuss.

In the US, spending has been out of control since the financial crisis, and the political climate is so toxic and polarised that any co-operation between Democrats and Republicans is limited to spending more money.

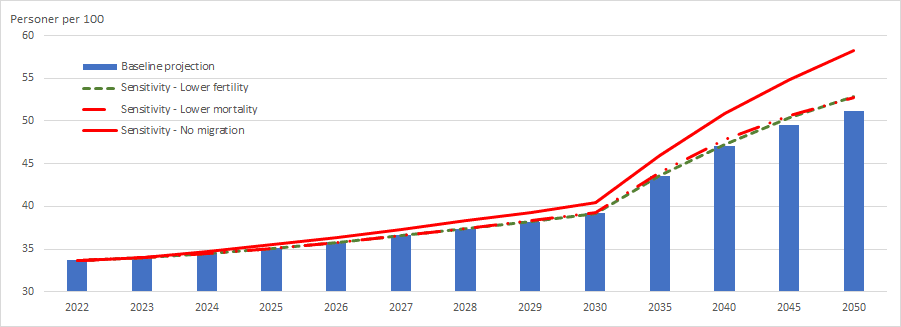

In the EU, there has been a lack of structural reforms during the last 10-20 years. An ageing population with more than 13 million baby boomers in Germany alone will be retiring over the coming 5-10 years, so the working population (15-64 years) will have to support a larger and larger group of retired people (65+), as seen in Figure 3, below.

Figure 3 Eurozone 65+ years to 15-64 years dependency ratio source Eurostat projection

Eurostat has made these demographic projections for the period from 2023 – 2100. We will focus on the eurozone and the period to 2050, as all EU countries are facing the same issue, differentiated only by the severity of the ageing phenomenon.

At the outset, however, one should question the Eurostat’s age-group parameters. In today’s society, hardly any of the 15-20 age group are fully in the work force, as they might have been 40 or 50 years ago. With an age group of 20-64, instead of 15-64, the dependency ratio would increase even more.

According to Eurostat, 33.7 persons of age 65+ are currently supported by 100 persons between 15 and 64. In Eurostat’s baseline projection, the numbers of 65+ will increase to more than 39 persons-per-hundred already in 2030, rising to almost 44 persons five years later and reaching 52 persons in 2050.

Unfortunately, there are few mitigating factors. Only a significant increase in the fertility rate would improve these projections. But several factors, alone or in any combination, would make the dependency ratio a lot worse, as seen from the sensitivity analysis provided by Eurostat (Figure 3, above):

- lower fertility makes the projection worse;

- lower mortality also makes the projection worse;

- no migration makes the projection a lot worse.

A much higher dependency rate, in combination with the public sector deficits in both Europe and the US that have been accumulating debt since the global financial crisis, and an aversion to implementing structural reforms, will place severe restrictions on public spending if nothing changes.

We are in a situation where solutions must be found in the next 5-10 years to address the issue of a rapidly ageing population, and its impact on the public sector and societal sustainability.

As we have shown previously, there is no unemployment pool to draw from, leaving only two viable options on the table:

- raise pensionable age thresholds, and/or

- increase migration,

These are extremely sensitive issues that hardly anyone dares discuss currently.

The facts, however, remain the same. If we want to be able to maintain the same standard of living and finance the green transformation, EU citizens need to retire much later and we need migration to continue.

Until this happens, we are indeed on borrowed time.