21/06/2024

Where is the EU after the European Parliament election?

Newsletter #71 - June 2024

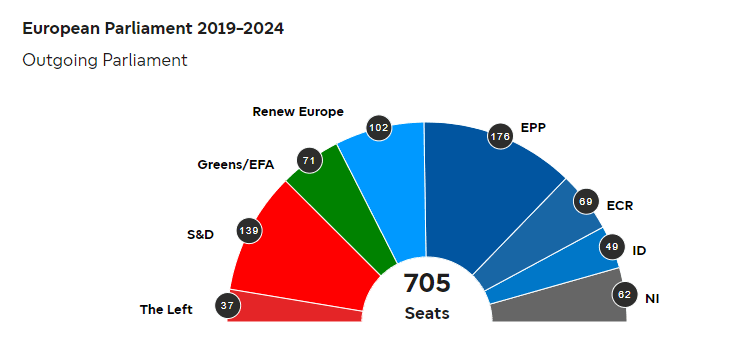

The outgoing and incoming European Parliament

Before the election, many observers expected a significant swing to the right in the European Parliament. However, while European voters did elect a slightly more right-leaning parliament, it was not on the scale that some had anticipated.

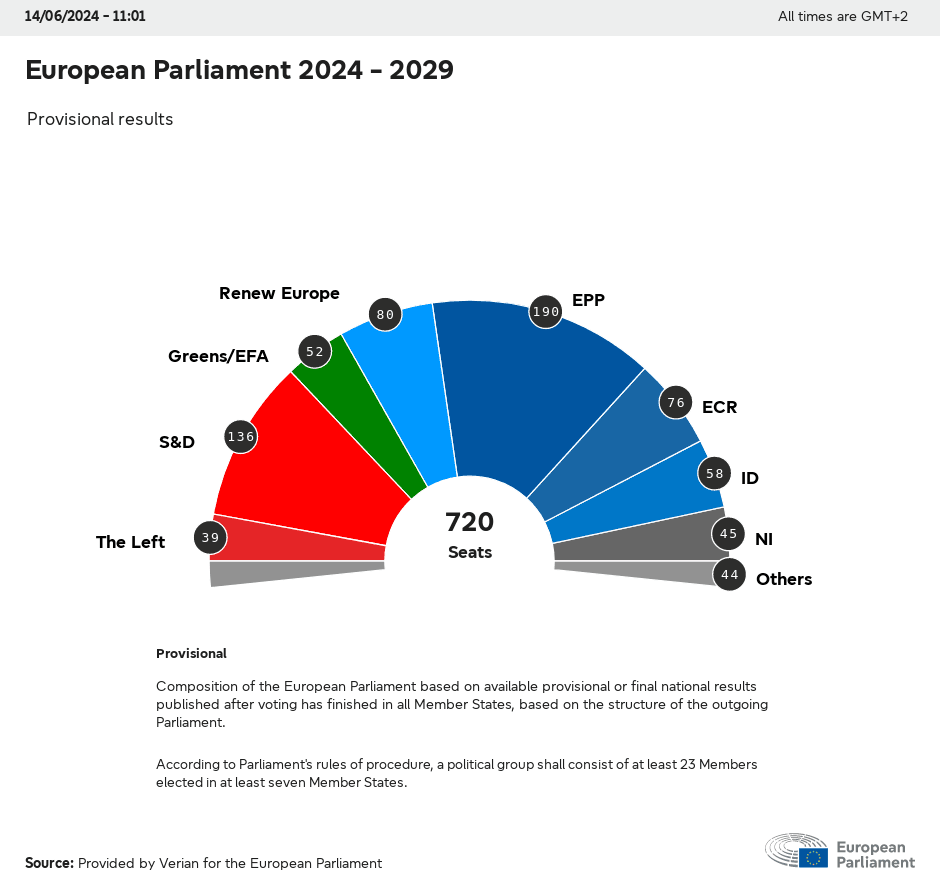

The EPP (European People’s Party), made up of Conservative and Christian Democrats, and the group that is supporting the candidature of Ursula von der Leyen to continue as head of the European Commission, gained 14 seats and now has 190.

The more right-leaning ECR (European Conservative and Reformist group) gained 11 seats and now has 76. This group includes Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni’s party.

The far-right group ID (Identity and Democracy) now has 58 seats, a gain of 9. This group is led by Marine Le Pen and her party, France’s Rassemblement National.

The S&D (Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats) lost a few members and now has 136 seats.

Renew Europe (the liberal group) which includes French president Emmanuel Macron’s party, and the Greens/EFA (European Free Alliance) were the big losers in this election. Renew lost 23 parliamentary seats and now have 80 members only a few more than ECR. The Greens lost 19 and are down to 52 MEPs.

After strong performances in the “climate” election of 2019, these two parties suffered in this year’s election, as climate-related issues have become less important for the majority of the electorate and President Macron’s domestic popularity has significantly diminished.

Figure 1 Outgoing European Parliament June 2024 Source European Parliament

On both sides of the new European Parliament, there are parties that have not yet joined a political faction (see Figure 2, below), but many will likely do so after negotiations with the various groups.

The NI (non-attached) members include Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party and Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland.

Figure 2 Incoming European Parliament Source European Parliament

How the European Parliament works

These political blocs are essentially the infrastructure of the European Parliament; each group must have at least 23 members of parliament (MEPs) and represent a minimum of seven different member states.

Depending on their relative representation in terms of MEPs, members of individual political groups are allocated positions on various committees, which may be in the form of chair of a committees, status as co-ordinator or “rapporteur”. MEPs thus selected lead the legislative process and the daily work of the European Parliament.

It is important for each national political party to join a political group in the European Parliament, otherwise they will stand on the sidelines without much influence.

Furthermore, the larger a political group’s representation in the parliamentary assembly, the greater the number of committee positions it will command. The selection for this is done by means of the so-called “d’Hondt” method, which uses a divisor to distribute posts after a political groups “ranking”.

In the d’Hondt method each political group starting with a divisor of 1 and every time a political group select a “post” their divisor increases with 1.

In the new European Parliament, the EPP is again the largest political group, with 190 members, so they will select first. Using the d’Hondt method, the EPP now has a divisor of 2, which equates to 95 members.

S&D is the second largest group with 136 MEPS, so they will select second. Thereafter they have a divisor of 2 which equates to 68 members.

Third to select will again be the EPP, as their 95 members are more than Renew’s 80. This process continues until all posts are distributed among the various political groups.

With this method of distributing posts, it will be some time before the far-right ID will be eligible to select posts. Fears of a far-right takeover of the European Parliament were therefore misplaced.

As the new European Parliament will continue pretty much as before the election, any potential political crisis in Europe will come from a completely different direction.

The real economic and political problem in France and Germany

COVID-19 and the following surge in inflation, combined with a lack of growth in both France and Germany, has polarized the two countries between those who have enough and those who feel that they are suffering from a decline in living standards.

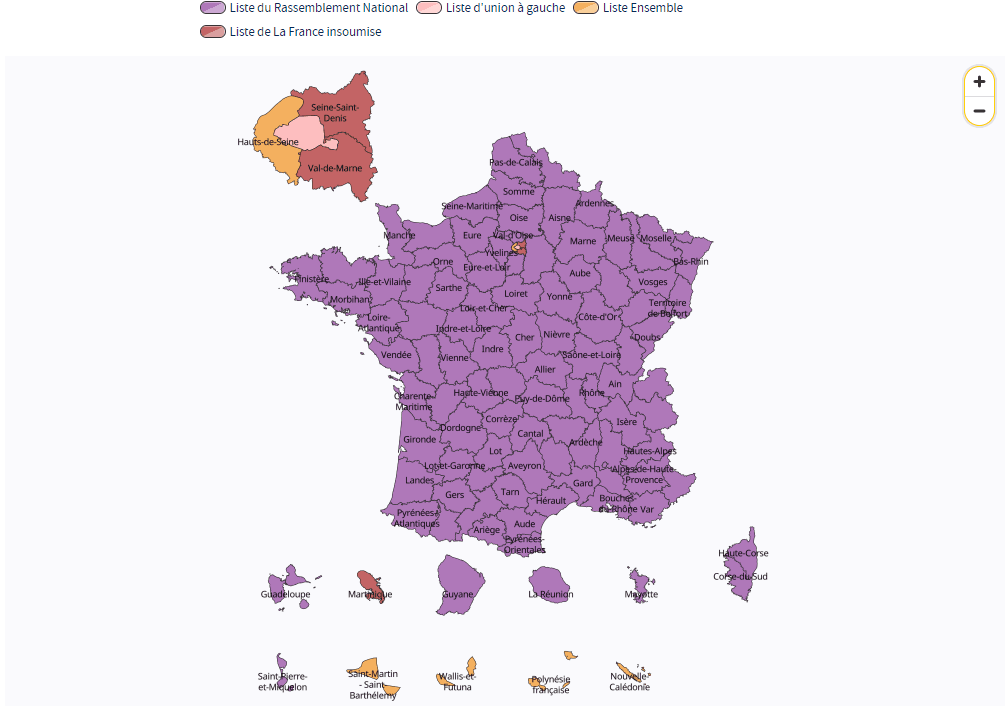

France

For France, the movement towards Marine Le Pen and the Rassemblement National (RA) is particularly striking. The RA became the largest party in every department outside Paris and excluding some overseas territories, as seen in Figure 3, below.

Figure 3 Largest party in EP 2024 per department in France source Le Figaro

French voters often use European Parliament elections as a proxy for expressing dissatisfaction with their current government and its policies.

This is why President Macron has now called a surprise French parliamentary election. If this gamble pays off to the benefit of Macron, it will enable him to form a new government without the RA; if it does not, then the political situation in France may develop into a stalemate that could threaten to undermine the efficacy of the EU as a whole.

Germany

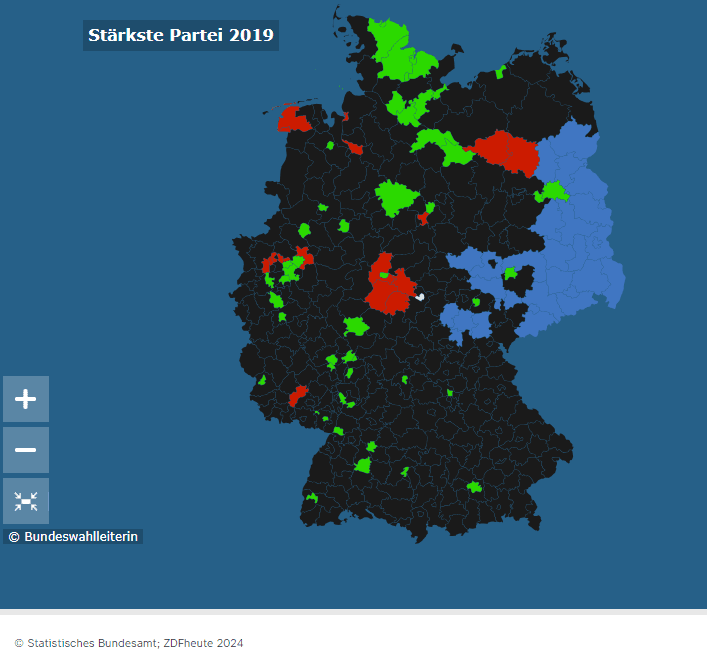

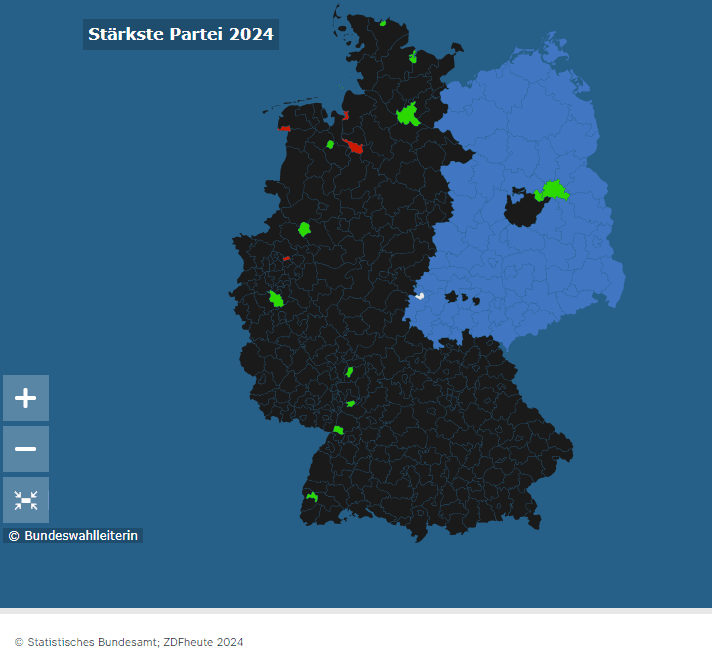

The development in Germany is equally striking. Here, the Alternative für Deutschland became the second-largest party, overtaking both the SPD (Social Democrats) and the Green Party. The conservative CDU/CSU alliance remains by far the largest party in Germany.

What is even more astounding is the stark change in Germany since the 2019 EP election (cf. Figures 4 and 5, below).

Figure 4 Largest party in EP 2019 per Kreis in Germany source ZDF

Figure 5 Largest party in EP 2024 per Kreis in Germany source ZDF

The SPD has basically been almost obliterated, retaining its hold only in Bremen, Bremerhaven and Emden. Even in the Ruhr region, the industrial heartland of Germany, the SPD remained the largest party in only one city, Herne.

Likewise, the Green Party only managed to maintain its prominence in some of the bigger cities, while the CDU/CSU became the largest party in almost the entire former West Germany – in stark contrast to the former East Germany (DDR), where, excluding Berlin and Potsdam, the AfD became the largest party.

In addition, the BSW, a new, left-leaning party, drew support away from the established parties, garnering around 6% of the total votes in the recent election. Fringe parties also did surprisingly well. This clearly signals that many people, especially in the former DDR, are disaffected, to say the least, with the politics of the current ruling coalition of SPD, FDP (Liberals) and Greens.

Impact from France and Germany on the EU

It is clear from the above charts that many people in both France and Germany living outside the big cities, i.e. the most deprived areas of both countries, have been searching for alternatives and have found that in various “populist” parties.

Both France and Germany are facing serious internal political problems, as their current governments appear to have lost touch completely with their respective electorates.

Before the European Parliament election, most observers feared that a move toward the far right might impede the workings of the EU. That will not be the case.

The real difficulty for the EU lies in the Berlin - Paris axis which, going forward, will have plenty of domestic problems to address.

It can become a real hindrance for any development in the EU if its main motor is not firing on all cylinders.

Impact from financial markets

What will be the impact on the financial markets of the current situation in France and Germany?

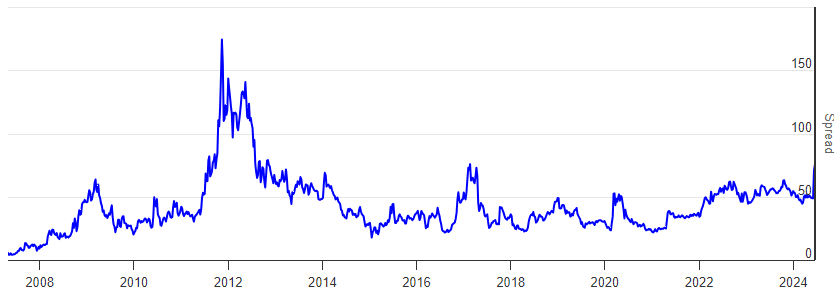

Figure 6 France - Germany 10-year bond spread (OAT-BUND) source Highcharts.com

That is difficult to answer. What is already remarkable is the widening of the spread between France and Germany on 10-year government bonds. After the European Parliament election, the 10-year government bond spread between France and Germany widened by more than 0.3% to over 0.8%.

Over the last 15 years, the spread has only once been above 0.8%, and that was during the Greek financial crisis.

If turmoil arises in the European government bond market again, and spreads start to widen even further, then the ECB will step in and try to stabilise these spreads.

The ECB will have to perform an amazing balancing act of lowering inflation, reducing its asset purchase programs and simultaneously stabilising government bond spreads.

This will be a complex, three-way balancing act for the ECB to perform. Most likely, at least one of these elements will go wrong, and the consequences for the financial markets will follow.