24/10/2024

Economic and political balancing acts

Newsletter #74 - September 2024

ECB lowers interest rates again

With inflation steadily decreasing across the eurozone, the ECB took the opportunity during its October meeting to reduce official interest rates by 0.25%.

Inflation in the eurozone has now reached 2%, which aligns with the ECB's target range and provides a strong rationale for the rate cut.

Nevertheless, ECB monetary policy remains a delicate balancing act, as fundamental macro data are pointing in different directions.

Lack of growth

Draghi's recent report to the EU Commission highlighted the longstanding disparity in productivity growth between the EU and the US, suggesting that substantial reforms are necessary to close this gap.

Full implementation of the single market would undoubtedly boost productivity, potentially spurring growth.

Since the financial crisis, growth across the EU, especially in the older member states, has been sluggish. This was one of the key reasons behind the ECB's policy of maintaining ultra-low interest rates and even enduring periods of negative rates.

Furthermore, many EU governments have been running substantial deficits for years in an attempt to stimulate growth, though with limited success.

However, one area where success has been evident is the labour market.

An extremely tight labour market

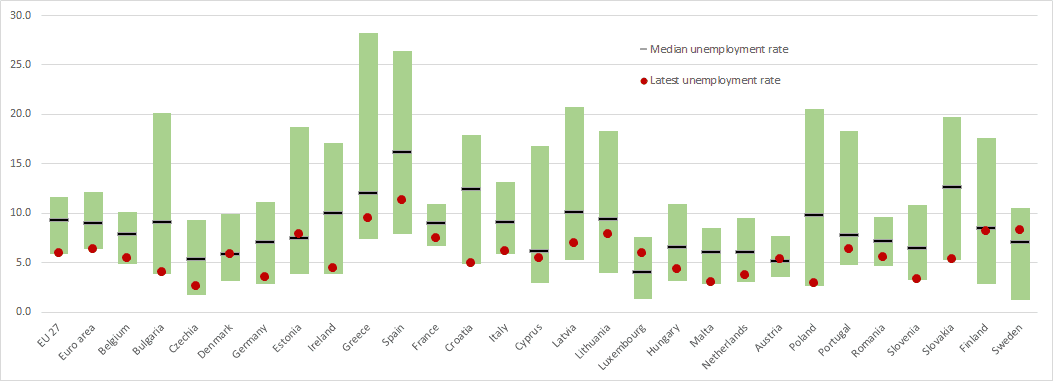

To illustrate the current tightness of the EU labour market, we have utilized Eurostat data dating back to 1983 (where available) and created a bar chart showing the minimum and maximum unemployment rates for each EU country over this period.

Figure 1 Unemployment rate band (min-max) since 1983 source Eurostat

To this chart, we have also added the median unemployment rate for each country as a reference point within their respective bar. When examining the most recent unemployment rates for the EU27 and the eurozone, it becomes apparent that we are near, if not at, the lowest unemployment rates since 1983.

Apart from Luxembourg, Sweden stands out as the only EU country with a recent observation well above its median unemployment rate. This can be explained by data from the Swedish Statistical Office’s Q2 2024 Labour Market Survey, which shows an unemployment rate of just 4% for Swedish-born employees, a rate consistent with most other EU nations.

Given that GDP can only grow through higher productivity, increased employment and extended working hours (or raising the retirement age), it is challenging to foresee high growth rates in the EU over the coming years unless significant changes, such as those proposed in Draghi’s report, are implemented.

Impact on public finances

The protracted lack of economic growth has severely impacted public finances. Despite historically low unemployment rates, many EU countries continue to struggle to balance their budgets, frequently running deficits as a result.

Germany, for example, is expected to experience its second consecutive year of recession, which will likely exacerbate its fiscal situation. Finance Minister Christian Lindner is expected to announce a €5 billion shortfall due to lower-than-expected tax revenues caused by sluggish growth.

Since the financial crisis, there has been a recurring tendency for governments to respond to economic challenges by enacting tax cuts or increasing public spending, further undermining the stability of public finances.

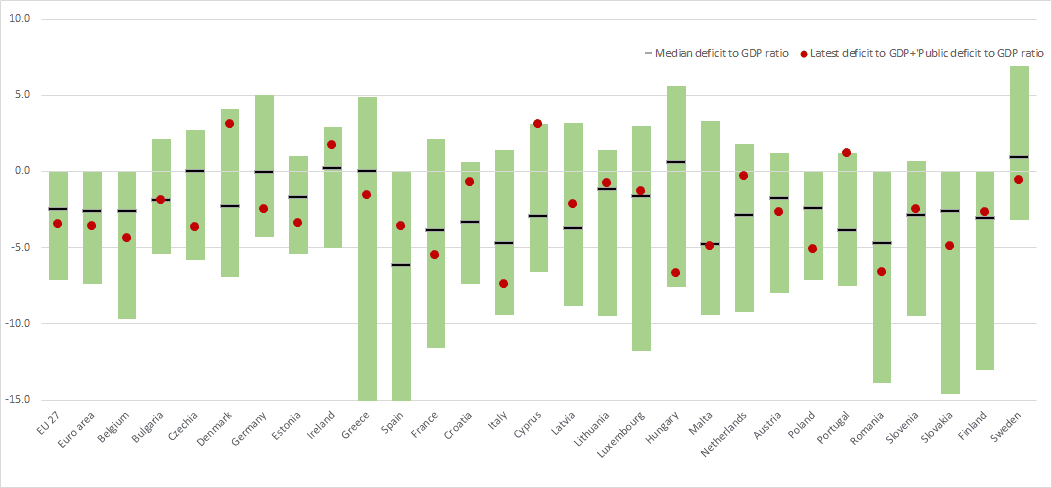

Figure 2 General government deficit band (min-max) from 1996 source Eurostat

Figure 2, above, vividly illustrates the structural deficit problem endemic in many EU countries. Even with record-low unemployment, few nations are close to balancing their budgets. Larger EU economies, such as Italy, France, Spain, Poland and Germany, have consistently exhibited fiscal laxity, running significant deficits over many years as a consequence.

The outcome of these long-standing lenient fiscal policies is that these countries’ debt levels are not far from their historical maximums for the period since 1996.

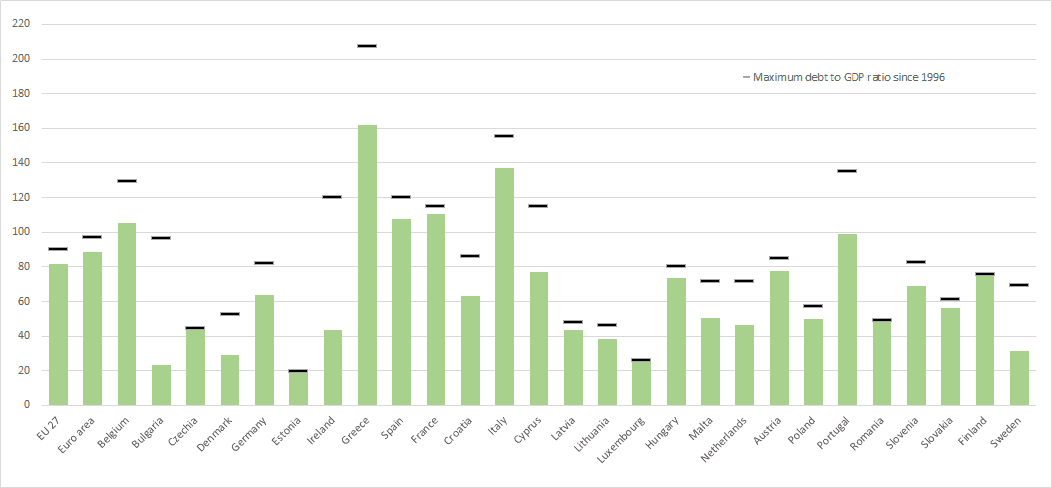

Figure 3 Current (2023) public debt to GDP ratio source Eurostat

Ironically, the countries most severely affected by the 2012 Greek financial crisis, namely Greece, Ireland and Portugal, have managed to significantly reduce their debt levels, demonstrating a notable fiscal turnaround.

Do not borrow from the future

If major EU countries such as Germany, France and Italy are unable to achieve balanced budgets in the current environment, it is difficult to see a sustainable path forward without structural reforms. When the next severe recession hits, deficits will once again balloon, and debt-to-GDP ratios will rapidly escalate to unsustainable levels.

To avert this outcome, comprehensive reforms must include both increased taxation and significant reductions in government spending, particularly in public transfers like pensions.

As the Draghi report underscores, sweeping changes are required at both the national and EU levels if the welfare system is to be preserved.

The EU and its member states must invest in the future, rather than continuing to effectively mortgage it, as is currently happening with the unchecked deficits in the public finances.