18/12/2024

Real interest rates - a real concern for the eurozone

Newsletter #76 - December 2024

Real interest rate - a game changer

Why has economic growth in the eurozone remained persistently low? As highlighted in earlier newsletters, economic growth originates from two fundamental sources: the number of hours worked by the labour force and gains in productivity. Both of these components are crucial to understanding the current stagnation.

At present, the European Union (EU) enjoys favourable labour market conditions, with employment levels at or near historical highs and unemployment rates at their lowest in decades. According to economic theory, the most productive individuals are typically employed first. Consequently, the marginal productivity of newly hired workers tends to decline as the labour pool expands. However, this principle alone does not adequately explain the absence of significant productivity gains across the EU.

This conundrum prompts a deeper examination of the investments made over the last 15 years. Could these investments have been less productive than those made in earlier decades? Additionally, could a significant shift in real interest rates within the EU have exacerbated the region's sluggish economic development?

German 10-year real interest rates: a historical perspective

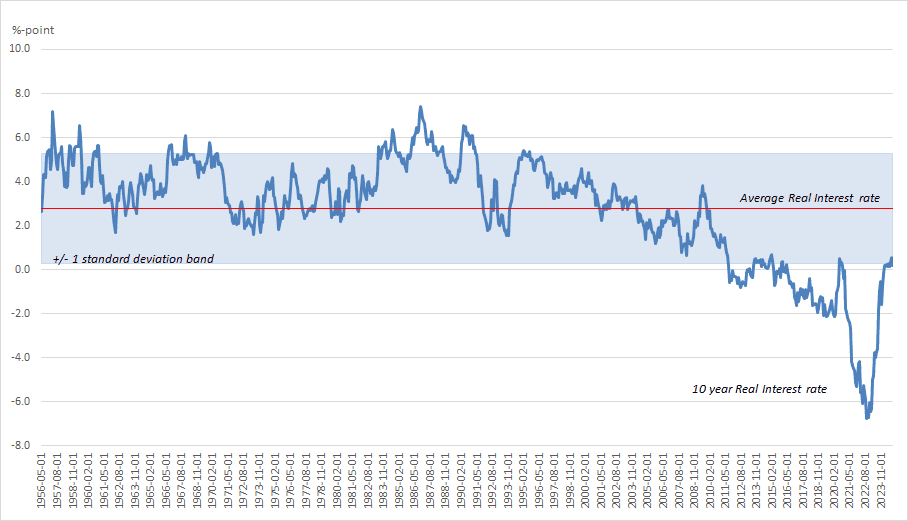

To explore the role of real interest rates, we analysed German 10-year real interest rates from 1956 to the present. Over this extensive period, the average real interest rate stood at 2.77%, with a standard deviation of 2.49%. These metrics, depicted in Figure 1, offer a comprehensive view of long-term trends.

Figure 1 German 10-year real interest rate since 1956 source FRED and Quantrom

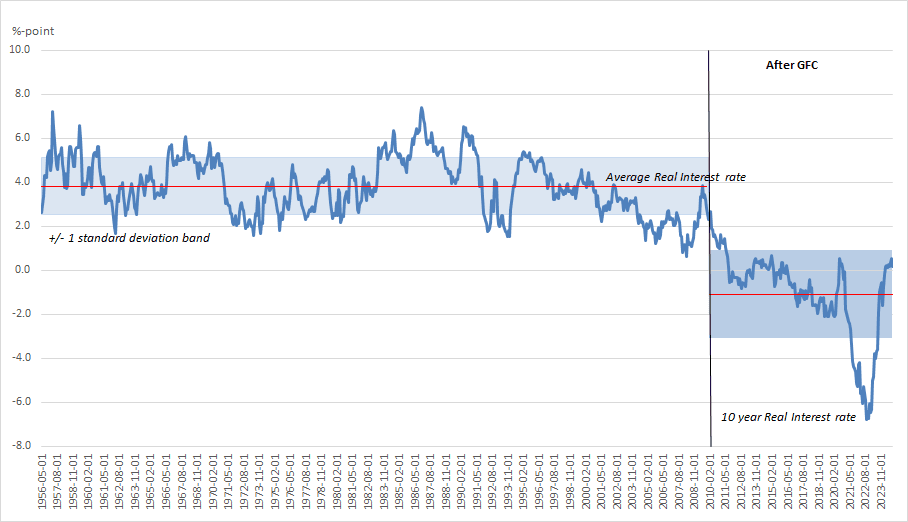

Figure 2 German 10-yr real int. rates before and after the GFC source FRED and Quantrom

A structural shift after the global financial crisis (GFC)

A closer look at the data reveals a notable structural change around 2010, shortly after the GFC. During this period, real interest rates on German 10-year bonds dropped to historically low levels, marking a departure from the norm observed over the preceding decades.

To better understand this shift, we divided the data into two periods, before and after the GFC, with 2009 serving as the dividing line. The recalculated averages are striking:

- before the GFC (1956–2009), the average real interest rate was 3.83%;

- after the GFC (from 2010 onwards, the average real interest rate plummeted to -1.08%.

This near 5-percentage-point drop in average real interest rates represents a profound shift, the implications of which still reverberate across the EU economy. Figure 2 (above) illustrates this divergence and underscores the unprecedented nature of the post-GFC era.

The effects of negative real interest rates

The European Central Bank (ECB), through its accommodative monetary policy, sought to stimulate additional investment while alleviating the interest burdens of countries with substantial public debt. While this approach provided short-term relief, its long-term effects raise significant concerns.

Insufficient government and private investment

The fiscal space created by historically low interest rates has predominantly been allocated to welfare programs rather than much-needed structural reforms. For instance, Germany has not implemented a major reform initiative since the Gerhard Schröder administration more than two decades ago. Similarly, investments in critical infrastructure and defence have been insufficient across much of the EU.

Private investment, expected to be bolstered by low borrowing costs, also failed to materialize in a transformative way. On the contrary, negative real interest rates may have led to a substantial misallocation of capital

Historically, investors holding German government bonds between 1956 and 2010 could expect an average real return of over 3.5%, providing a benchmark for evaluating other investment opportunities. With real returns turning negative post-GFC, investors sought alternative avenues, most notably equities, where returns derive from either dividends or capital gains.

As more investors poured into equities, dividend yields fell, leaving capital gains as the primary source of returns. This dynamic pushed investors further out on the risk spectrum, often leading to investments that could only be justified under overly optimistic assumptions. In many cases, this created a misallocation of resources, prioritizing politically driven but economically questionable projects over those capable of delivering sustainable productivity gains.

Distortions in economic valuations

In an environment of persistently low real interest rates, long-term economic assumptions became distorted. For example, many investment cases relied on the assumption that long-term interest rates would remain between 1% and 2%, with inflation hovering around 2%. These conditions allowed small positive cash flows to justify inflated valuations, further exacerbating inefficiencies.

Returning to positive real interest rates

The evidence from the past 15 years highlights the limitations of loose monetary policy in addressing structural challenges. True reform requires decisive governmental action, including difficult decisions and transparent communication with the electorate about the necessity of such measures.

The ECB might benefit from revisiting the Bundesbank’s successful strategy, which maintained positive real interest rates alongside an upward-sloping yield curve for over four decades. This approach fostered sustainable growth and prudent investment decisions, providing a model worth emulating.

ECB's recent policy decisions: a missed opportunity

Despite inflationary pressures beginning to re-emerge, the ECB announced yet another 0.25% reduction in official interest rates at its December meeting. This decision reflects a continued reliance on monetary easing, even as its effectiveness in stimulating growth remains questionable.

ECB's economic forecast: more of the same

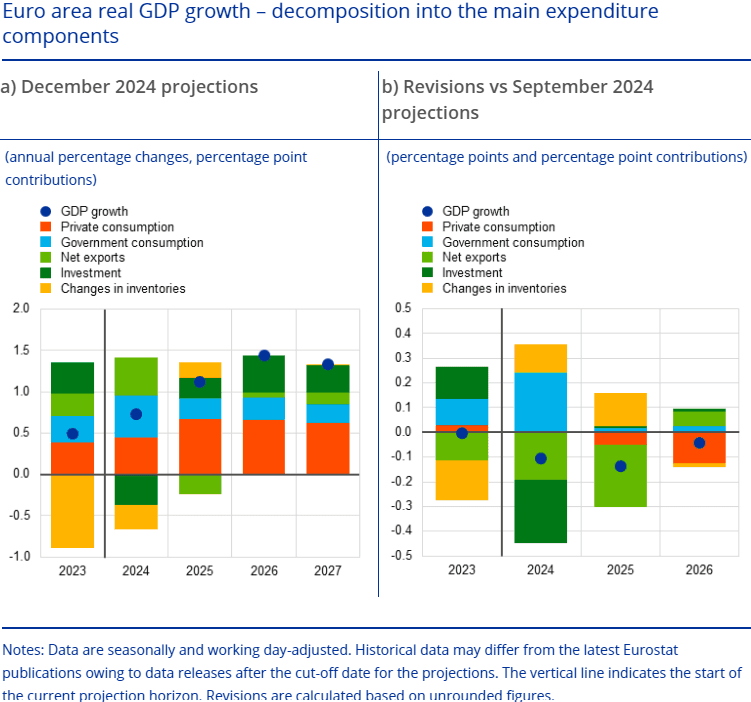

The ECB staff's December projection paints a sobering picture for the eurozone. Headline inflation is expected to exceed the 2% target for much of the forecast period through 2027, while economic growth is anticipated to remain modest, at 1% to 1.5% annually. The growth will primarily rely on private and government consumption, with net exports and investments contributing only marginally (see Figure 3, below).

The projection assumes stable global trade tariffs. However, potential tariff escalations, such as those announced by the US, could severely impact the EU, one of the world’s largest net exporters. This would lead to a significant drop in exports, lower overall growth and higher inflation.

Figure 3 ECB staff projection for GDP growth - December 2025

Conclusion

The ECB's forecasts and policies suggest little departure from the stagnation observed over the past 15 years. Without meaningful structural and fiscal reforms, the eurozone risks prolonged economic malaise. Policymakers must heed the lessons of recent history and take bold, transformative action to address the root causes of the region's economic challenges. The hope remains that initiatives inspired by Mario Draghi’s recommendations will eventually catalyze the necessary changes.

End of 2024

Finally, we would like to wish you a Merry Christmas and a prosperous 2025.