24/10/2025

Debt ratio and the Fifth Republic

Newsletter #85 - October 2025

In our previous newsletter, we examined the differences between countries in the ways they generate public revenue and allocate their expenditures. Although the mechanisms for collecting revenue and disbursing public funds vary considerably across nations, one conclusion remains constant: regardless of the chosen fiscal framework, maintaining strict budgetary discipline is essential to prevent public debt from spiralling beyond sustainable limits.

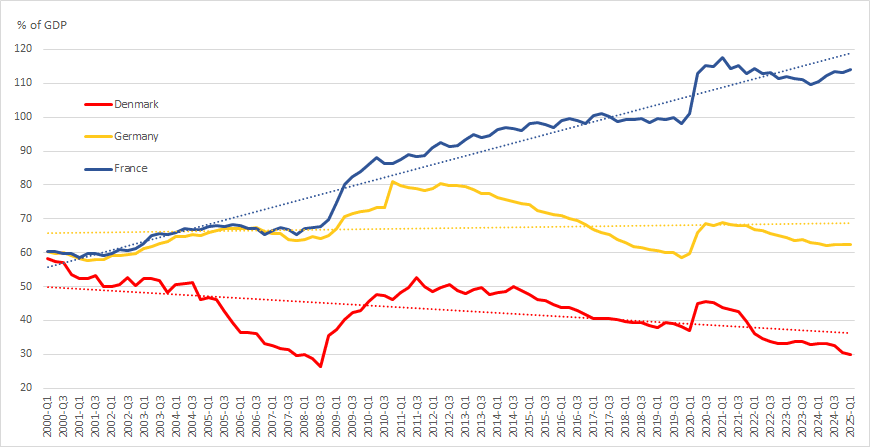

Figure 1 Debt to GDP ratio

Debt-to-GDP: three distinct trajectories

In the case at hand, Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the debt-to-GDP ratio since the year 2000 for France, Germany and Denmark.

At the outset of the period, the debt levels of all three countries were approximately identical, hovering around 60 percent of GDP. Since then, however, the trajectories have diverged markedly, reflecting distinct fiscal policies, economic conditions and approaches to public finance management.

Denmark

Even before the financial crisis of 2008–2009, Denmark had implemented substantial reforms to both its labour market and pension system. These measures placed the country on a trajectory of steady economic growth, accompanied by modest fiscal deficits - or, in some years, even surpluses - in the general government budget.

During both the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, Denmark’s debt-to-GDP ratio temporarily increased, as the government prudently expanded public spending to cushion the economy from severe recessions. However, once these crises subsided, fiscal discipline swiftly re-emerged, and the debt ratio began to decline again.

Over the subsequent years, Denmark has continued to pursue structural reforms, notably through the gradual increase of the statutory retirement age and other measures aimed at enhancing long-term fiscal sustainability.

Germany

Germany, in contrast, has followed a markedly different trajectory. Since the adoption of the “Hartz IV” reform, passed by the Bundestag in 2003 and implemented in 2005, the country has not undertaken any major structural reforms in either the labour market or the pension system.

In 2009, Germany amended its constitution (Grundgesetz, Articles 109 and 115) to introduce a constitutional “debt brake” (Schuldenbremse), stipulating that the federal government may not run a structural deficit exceeding 0.35 percent of GDP. The motivation for this amendment stemmed from the fact that Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio had surpassed the 60 percent ceiling set by the Maastricht Criteria.

This rule has effectively stabilized the debt ratio at around 60 percent, as shown in Figure 1. Yet, while simple and transparent rules are politically appealing, they can also have significant adverse effects on economic behaviour. Because mandatory expenditures and entitlement programmes typically account for more than 80 percent of general government budgets, the remaining fiscal space is often squeezed, leading to cuts in administrative spending and, more critically, in public investment.

Explanation 1:

Mandatory expenditures, such as education, childcare, defence, and interest payments on public debt, are typically governed by long-term legislation and therefore cannot be easily adjusted from one fiscal year to the next. Entitlements, on the other hand, represent legally guaranteed benefits, including pensions, unemployment benefits and social transfers, to which eligible citizens have an established right. Together, these categories consume the vast majority of government spending and leave limited room for policy manoeuvre.

To illustrate this fiscal conundrum, imagine that pensions account for 15 percent of the total general government budget. Suppose rising living costs lead to political pressure to increase pension benefits beyond inflation. At the same time, demographic changes cause the number of pensioners to rise, resulting in a combined additional expenditure equal to 2 percent of the total budget. Pensions now absorb 17 percent of government spending.

Initially, 20 percent of the budget was allocated to administration and investment, while the remaining 80 percent was locked into mandatory and entitlement spending. Under a debt brake (Schuldenbremse), the government is legally prohibited from running a higher deficit. Consequently, it must offset the 2 percent increase in pension expenditure by cutting elsewhere.

At first glance, a 2 percent reduction may appear modest. However, because it must be absorbed entirely by the ‘flexible’ portion of the budget (just 20 percent of total spending) the effective cut amounts to 10 percent of administrative and investment expenditures.

That is an entirely different magnitude: a fiscal tightening that directly undermines public-sector capacity and long-term investment potential.

As Germany’s population continues to age, entitlement costs have risen steadily, crowding out expenditures that could otherwise foster long-term growth. The result has been a prolonged period of stagnating economic activity, albeit with a stable debt-to-GDP ratio.

This structural imbalance has posed a persistent challenge for Germany. The new government under Friedrich Merz has partially relaxed the Schuldenbremse to allow for increased defence spending and investment in essential infrastructure projects.

Nevertheless, the pension burden on public finances continues to rise, and there has thus far been insufficient political appetite for undertaking the comprehensive structural reforms required to restore sustainable public finances.

France

Until 2009, and the onset of the global financial crisis, France and Germany maintained almost identical debt-to-GDP ratios. Over the past fifteen years, however, their fiscal trajectories have diverged dramatically. During this period, France’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from around 60 percent to approximately 114 percent, effectively doubling.

This development reflects the combined effect of two structural weaknesses: first, the absence of far-reaching reforms comparable to those implemented in Denmark; and second, the lack of fiscal constraints such as Germany’s constitutional deficit rule. The result has been a steady accumulation of public debt without corresponding improvements in growth potential or fiscal resilience.

Rising yield spreads: France versus Germany

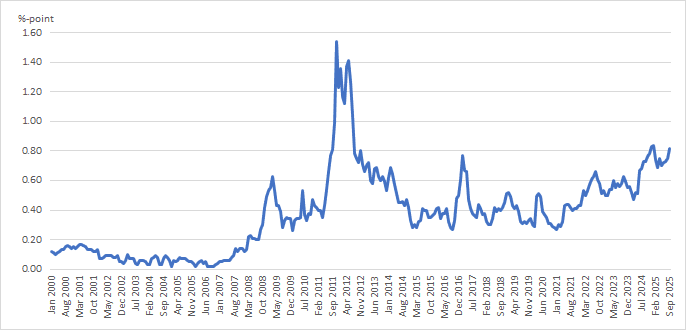

The growing debt burden has now become visible in financial markets, as shown by the widening spread between French and German 10-year government bond yields, illustrated in Figure 2

Figure 2 10-year bond spread France - Germany (source ECB)

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the yield spread was minimal, typically below 0.2 percentage points and at times virtually zero. However, during the Greek sovereign debt crisis in 2012, investors began to focus more closely on France’s underlying fiscal vulnerabilities. Although the spread temporarily narrowed again to around 0.4 percentage points, it has since trended upwards.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, France has faced a series of domestic political crises while failing to address long-standing structural economic issues. Consequently, the 10-year yield spread vis-à-vis Germany has continued to widen, reflecting both diminished investor confidence and the growing perception of fiscal divergence within the eurozone.

The French pension system

As discussed in our previous newsletter (No. 84, September 2025), France allocates more than 23.3 percent of its GDP to social protection, which is almost four percentage points higher than both Germany and Denmark.

The primary factor behind this discrepancy lies in retirement policy. According to CLEISS (Law No. 2023-270 of 14 April 2023), the statutory retirement age in France is currently 62 years, but is scheduled to increase to 64 for individuals born in or after 1968. By contrast, the official retirement age in Denmark is 68 for those born in or before 1966, and will rise to 70 for individuals born after 1970.

Moreover, French workers can retire even earlier through the “long-career early retirement” provision, provided they have contributed to the system for 168 quarters (42 years). Under this arrangement, they may retire as early as age 58. Although official statistics on early retirement are scarce, anecdotal evidence and sample data suggest that the effective average retirement age in France is closer to 60 years.

This represents a substantial gap of roughly six years between France and Denmark in official terms, and likely an even greater difference in practice. For French public finances, the implications are profound: the general government forfeits approximately six additional years of income tax contributions, while simultaneously incurring six more years of pension payments compared with, Denmark, where life expectancy is nearly identical.

Compounding the issue, Denmark’s pension framework is largely financed through defined-contribution schemes, funded by both employers and employees. In contrast, France relies predominantly on a pay-as-you-go system, which depends on current workers to finance the pensions of retirees. This structural design exposes the French system to severe fiscal strain as the population ages and the worker-to-retiree ratio continues to decline.

The fiscal outlook is therefore highly challenging, particularly given the political resistance to meaningful structural reform. According to a recent report in The Guardian, Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu has even offered to withdraw the planned increase in the retirement age from 62 to 64 years in negotiations with the Socialist Party, a move that underscores the enduring political sensitivity surrounding pension reform in France.

The end of the Fifth French Republic?

The political landscape in France has become increasingly fragmented, with the country’s three principal political blocs (President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist-liberal coalition, the right-wing Rassemblement National led by Marine Le Pen and Jordan Bardella, and the left-wing alliance under Jean-Luc Mélenchon of La France Insoumise) proving incapable of forging the compromises necessary to enact long-overdue structural reforms.

At present, the only shared position among these factions appears to be a determination to prevent one another from achieving any meaningful success. In the absence of political cooperation and reform momentum, the public deficit is likely to remain at its current elevated level or even widen further. Such a trajectory risks pushing France’s sovereign debt toward an unsustainable path, with potentially destabilizing consequences for both domestic and European financial stability.

Should this political paralysis persist, it could ultimately undermine the institutional foundations of the Fifth Republic, plunging France into a constitutional crisis that would need to be resolved before any comprehensive reform agenda could be implemented.

This is not only bad news for France itself, but also for the European Union more broadly. A prolonged period of French political and fiscal instability would deprive the Union of half of its traditional Franco-German leadership axis - the partnership that has historically served as the engine of European integration and policy coordination.

End game

Without decisive leadership and the courage to confront reality, France risks drifting into fiscal paralysis and political deadlock. The Fifth Republic may not collapse with a bang, but through gradual institutional suffocation, taking much of Europe’s momentum down with it.

France now stands at a crossroads: reform or decline.