19/12/2025

House of Cards

Newsletter #87 - December 2025

FOMC meeting in December 2025

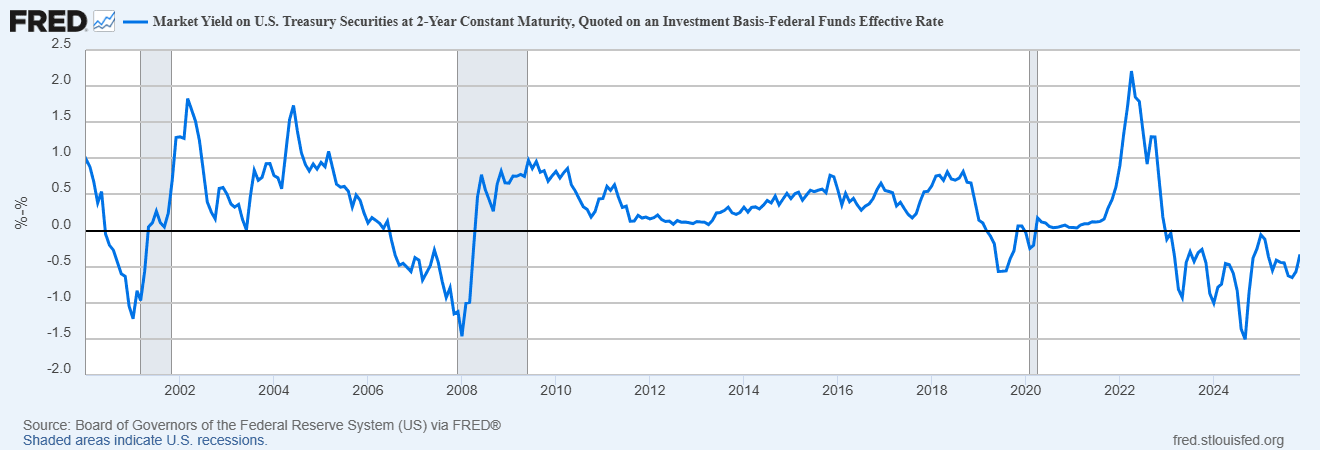

At its final meeting of 2025, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) delivered a widely anticipated policy adjustment by lowering the federal funds target rate by an additional 25 basis points, a move that was fully priced in by financial markets ahead of the decision. With this reduction, the effective policy rate has now converged toward the yield level of the 2-year US Treasury, a development that signals a growing alignment between Federal Reserve policy settings and prevailing fixed-income market expectations.

This convergence is particularly notable in light of the current negative spread between the 2-year US Treasury yield and the federal funds rate, which stands at approximately –30 basis points. Historically, such an inversion has been a reliable indicator that monetary policy remains marginally restrictive relative to short-term market rates, thereby leaving room for further policy accommodation. On this basis, we assess that the Federal Reserve may still implement an additional 25 to 50 basis points of cumulative rate cuts over upcoming meetings, should macroeconomic conditions evolve in line with current forecasts.

That said, while limited further easing remains plausible, market pricing suggests that the bulk of the monetary adjustment cycle is now largely complete. Forward curves imply that investors do not expect any further material or sustained deviations in policy rates beyond these incremental moves, reflecting a broader consensus that the Federal Reserve is approaching its estimated neutral rate.

Figure 1 Spread between 2-year US treasuries and Fed Fund rates

Steeping of the yield curve

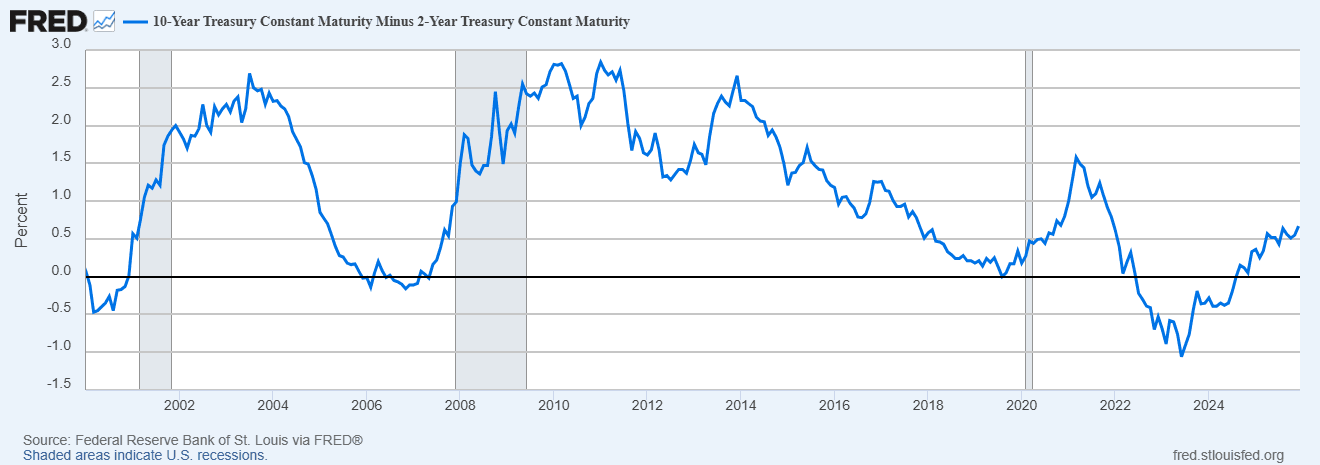

The persistence of elevated long-term yields despite a clear easing cycle at the front end, raises an important and somewhat concerning question regarding the underlying drivers of the current yield curve configuration. Ordinarily, a policy-driven decline in short-term rates is accompanied by a parallel, albeit typically more muted, downward adjustment in longer-dated yields as expectations for future growth and inflation are revised lower. However, this traditional transmission mechanism has notably failed to materialise in the current cycle.

Figure 2 Spread between 10-year and 2-year US Treasuries

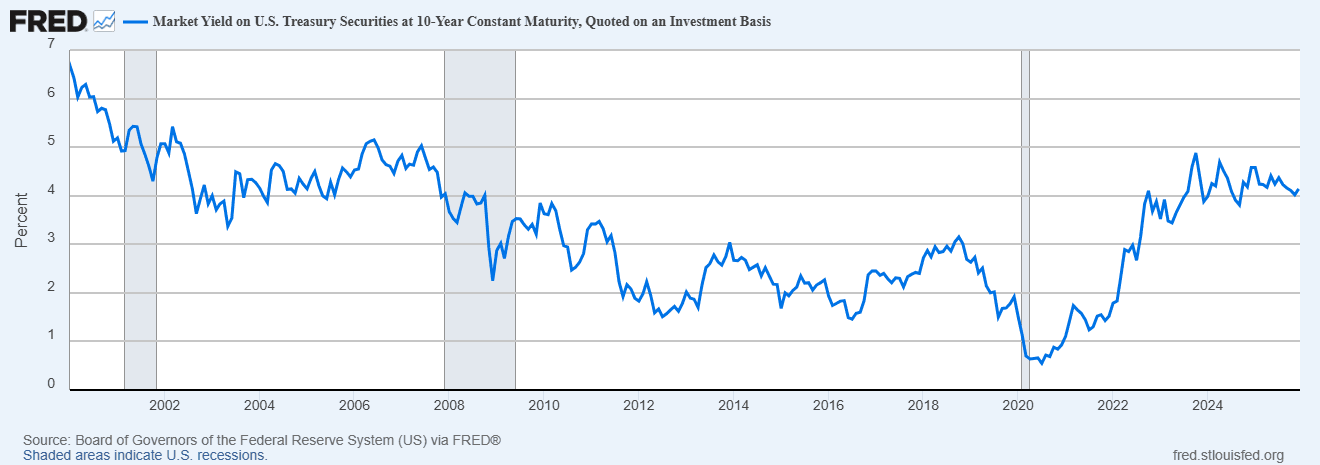

Since late 2022, the yield on the 10-year US Treasury has remained broadly anchored just above the 4 percent level, exhibiting remarkably limited sensitivity to changes in the federal funds rate. This rigidity strongly suggests that forces other than expected policy rates are dominating the pricing of long-term government debt. In practice, this implies that either the inflation risk premium or the term premium embedded in long-duration Treasuries (or a combination of both) has increased materially relative to historical norms during periods of monetary easing.

Figure 3 Interest rate 10-year US Treasuries

Some structural factors appear to be contributing to this development. First, inflation expectations may no longer be fully anchored at the Federal Reserve’s stated 2 percent target. While headline inflation has moderated from its peak, underlying price dynamics, particularly in services and labour-intensive sectors, remain sufficiently elevated to raise doubts about a full and durable return to target. As a result, investors may be demanding additional compensation for the risk that inflation stabilises at a structurally higher level than that which prevailed during the pre-pandemic period.

Second, the US Treasury market increasingly appears to be pricing in fiscal sustainability risks. Persistently large federal budget deficits, combined with a rapidly rising public debt stock, have altered the supply–demand balance at the long end of the curve. Investors may therefore require a higher yield to absorb the growing volume of long-term issuance, reflecting heightened concerns around debt dynamics rather than near-term monetary policy.

Partially offsetting these pressures (as discussed in a previous Quantrom newsletter) the US Treasury has strategically shifted issuance toward shorter-dated Treasury bills rather than longer-maturity bonds. While this adjustment has helped contain the government’s immediate interest expense and provided some support to long-term yields, it has not been sufficient to fully counteract the upward pressure stemming from elevated term premia.

Overall, the current configuration of the US yield curve is not particularly encouraging. A steepening driven primarily by falling short-term rates rather than declining long-term yields suggests that financial conditions may remain tighter than headline policy rates alone would imply. Over time, this dynamic has the potential to exert significant influence across asset classes, particularly in equity valuation, credit markets, and global capital flows, and may represent a latent source of market instability at a later stage of the cycle.

The impact on private credits

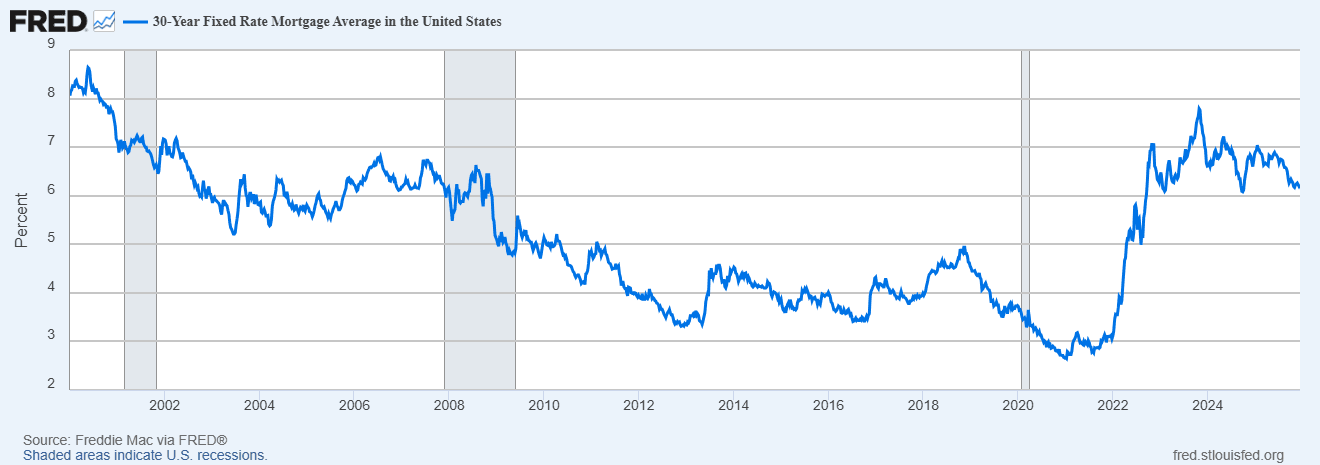

The limited pass-through from monetary easing to household borrowing costs underscores a fundamental disconnect between policy rates and effective financial conditions faced by US consumers. Despite a cumulative reduction in the federal funds rate, the 30-year fixed mortgage rate has remained stubbornly elevated, hovering at or above the 6 percent level. This persistence reflects the dominance of long-term Treasury yields and mortgage-specific risk premia in pricing housing finance, rather than short-term policy rates.

The implications for the US housing market are material. A large share of homeowners who originated mortgages during the 2010–2022 period remain locked into rates well below current market levels. For these households, relocating would often imply a substantial increase in monthly interest payments, in some cases approaching a doubling of debt-servicing costs. This so-called “lock-in effect” has significantly reduced housing turnover, constrained supply in the existing home market, and dampened overall transaction volumes, even in the presence of resilient demographic demand.

Figure 4 Interest rate on 30-year US mortgage loan

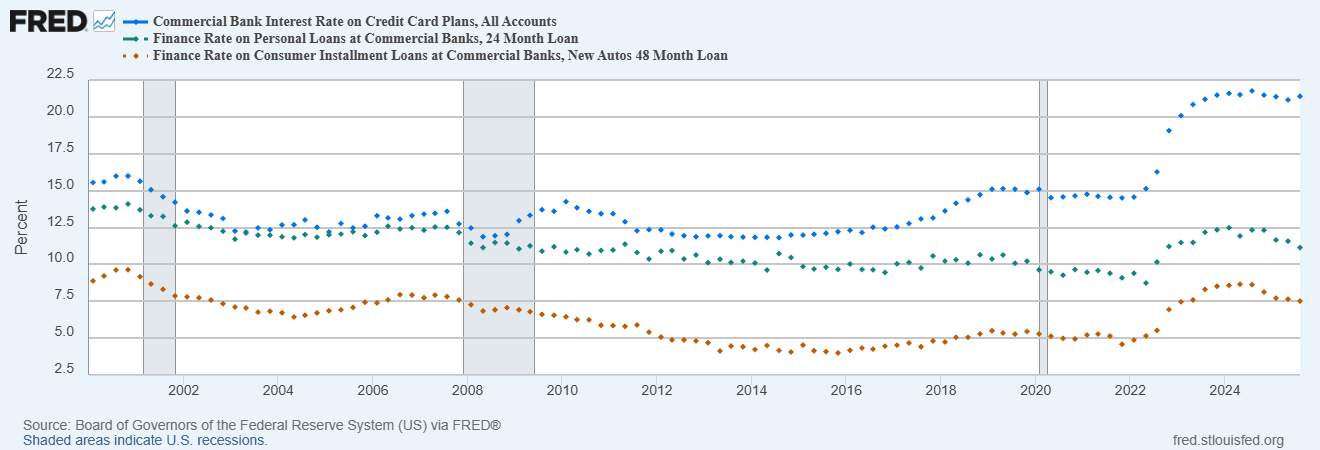

A similar pattern is observable across other segments of consumer credit. Interest rates on auto loans, consumer instalment loans and credit cards have declined only marginally, if at all, since the onset of the easing cycle. Most notably, credit card interest rates remain largely unchanged at historically elevated levels, indicating that lenders continue to price in a high degree of default risk and balance-sheet uncertainty. This asymmetric transmission suggests that credit spreads, rather than benchmark rates, remain the dominant determinant of borrowing costs for households.

From a broader perspective, the consumer credit market is delivering a markedly different signal than monetary policy rhetoric might imply. Credit providers are clearly demanding substantial compensation for credit and duration risk, reflecting concerns over household balance sheets, the sustainability of consumption growth and the potential lagged effects of prior monetary tightening. In this sense, the credit market is effectively acting as a brake on economic activity, offsetting part of the intended stimulative impact of lower policy rates.

Figure 5 Interest rates on different US consumer credits

Taken together, these developments imply that financial conditions for US households remain considerably tighter than suggested by headline rate cuts alone. As long as long-term yields and credit risk premia remain elevated, the transmission of monetary easing to the real economy is likely to remain incomplete, increasing the risk that consumer-driven growth slows more abruptly than policymakers currently anticipate

Wall Street vs Main Street vs Pennsylvania Avenue

US monetary and fiscal policy increasingly appears to be pulled in three different directions, reflecting competing priorities between financial markets, households and the federal government. In recent quarters, the Federal Reserve has continued to accommodate Wall Street by ensuring ample liquidity conditions. This has occurred first through the effective suspension of quantitative tightening (QT) and more recently through the introduction of targeted programs aimed at purchasing short-dated Treasury bills. While these measures are framed as technical adjustments to market functioning, their net effect has been to stabilise funding markets and support asset prices.

At the same time, policy decisions have also been shaped by the interests of Pennsylvania Avenue - the address of the White House and, more importantly in this context, the US Treasury. Lower policy rates directly reduce the government’s interest burden on an ever-expanding stock of outstanding debt. This fiscal motivation helps explain the political pressure for lower interest rates, even in an environment where inflation remains above the Federal Reserve’s stated 2 percent target. President Trump’s repeated calls for policy rates near 1 percent should be interpreted through this lens: at current debt levels, even modest changes in interest rates translate into hundreds of billions of dollars in annual debt-servicing costs for the Treasury.

In contrast, Main Street has seen little tangible relief. Despite policy easing, borrowing costs faced by ordinary households remain elevated, as documented in mortgage and consumer credit markets. Unlike Wall Street, which has benefited from rising asset prices and abundant liquidity, the median household - particularly those without significant financial assets - continues to face high financing costs and declining affordability. This divergence has amplified perceptions of economic unfairness and weakened the effectiveness of monetary policy as a broad-based stabilisation tool.

House of cards

The deeper, structural issue confronting the US economy is its increasing bifurcation. Economic gains have become heavily concentrated among a narrow group of large corporations and the top decile of households, who benefit disproportionately from fiscal transfers, accommodative monetary policy and rising financial asset valuations. Meanwhile, large segments of the population face stagnant real incomes, elevated debt-servicing costs and limited access to the upside generated by asset inflation.

This imbalance leaves the system increasingly fragile. If - and this is a critical conditional - the long end of the Treasury yield curve continues to reprice higher, the consequences could be severe. A sustained move of the 10-year Treasury yield above 5 percent and the 30-year yield above 6 percent would materially tighten financial conditions across the economy. Such a shift would raise borrowing costs for the federal government, corporates and households simultaneously, while also placing downward pressure on equity valuations and real estate prices.

Under these conditions, it would not require a large additional shock for the current equilibrium to unravel. With fiscal deficits elevated, monetary policy constrained and household balance sheets already under strain, the US economy increasingly resembles a house of cards: stable for now, but highly vulnerable to a disorderly adjustment should investor confidence erode further.